http://www.eventbrite.com

Tickets

Event Information

High Business is the club you want to join if you are looking for a two in one social but business group. Stimulate your mind and talk moves

About this Event

Due To Covid-19, we can only allow interested people to purchase two tickets only. Reality Management can not host large parties due to the still growing number of the virus. If you are looking to come with more than one guest, you must allow the guest to purchase their tickets.

Reality Management presents High Business; High Business is the club you want to join if you are looking for a two in one social but Business group. Stimulate your mind and talk Business with like-minded people. Learn from entrepreneurs who mastered different industries and learn how to get into the cannabis industry, one of the hardest industries to get into today. The Canibus industry is similar to the housing market in the 80s, and you don’t want to miss out on this type of business group. No need to sell anything we support each other with an event in your state once a month.

Admission Offers

When you buy a ticket to enter the event of “Reality Management Presents High Business,” depending on the ticket admission purchased, you will receive different opportunities depending on the level of admissions purchase.

Reggie Admission: Gives you access to the event, allowing you to purchase from the vendors and network with like-minded people. (Sponsor) Rich For Families Foundation offers a free generational wealth gameplan offering free life and health insurance, credit repair tools, and much more.

Gas Admission: Gives you access to the event, allowing you to purchase from the vendors and network with like-minded people. High Business T-shirt, access to the High Business business club, one meal ticket to a free dinner. (Sponsor) Rich For Families Foundation offers an open generational wealth gameplan offering free life and health insurance, credit repair tools, and much more.

Loud Admission: Gives you access to the event, allowing you to purchase from the vendors and network with like-minded people. High Business T-shirt, access to the High Business business club, one meal ticket to a free dinner, A High Business gift bag that comes with one thing from each vendor, and access to Reality Management after party. *Loud members get one prerolled flower* (Sponsor) Rich For Families Foundation offers an open generational wealth gameplan offering free life and health insurance, credit repair tools, and much more.

Exotic Admission: Gives you access to the event, allowing you to purchase from the vendors and network with like-minded people. An Exotic High Business T-shirt, access to the High Business business club, one meal ticket to a free dinner, A High Business gift bag comes with one thing from each vendor, and access to Reality Management after party. *Exotic members Joins the 100 preroll flower cipher* (Sponsor) Rich For Families Foundation offers an open generational wealth gameplan offering free life and health insurance, credit repair tools, and much more.

Police Free Schools

https://www.urbedadvocates.org/policefreeschools

https://www.npr.org/2020/06/23/881608999/why-theres-a-push-to-get-police-out-of-schools

Philly school board hearing report: speakers seek fewer police, more support services

This article originally appeared on The Notebook.

—

Teachers, counselors, parents, and national activists added their voices to students’ call for “police-free schools” at a general public hearing held by Philadelphia’s Board of Education on Thursday.

The board holds two of these hearings annually, as the City Charter mandates; the only agenda for the meetings is to hear speakers.

At the hearing and at a virtual “rally” held during the hour before, members of the Philadelphia Student Union and their allies repeatedly said that reform of the District’s 350-plus-member school security staff was not enough. Speakers called for the “radical step” of removing school police and redirecting funds to counseling and social services personnel.

“It’s time to reimagine safety in schools without policing,” said Saudia Durrant, an organizer with PSU. She and others urged the District to “stand up against institutional racism,” pointing to statistics showing that school police are more likely to be in schools with more Black and brown students, who are disproportionately disciplined across the country.

“Please, please, please, look at the research, look at the statistics, and you’ll find that they align perfectly with the experiences of your students and that police do not belong in our schools,” said Masterman senior and PSU member Aden Gonzales. “With the current amount of money spent on police, we could hire over 500 guidance counselors.”

Some spoke of indignities they suffered at the hands of school police. Allison Fortenbery, a rising senior at Masterman, recalled being stopped and searched with a long line of people waiting behind her at a metal detector because the officer thought an outline in her backpack was a prohibited e-cigarette.

“It was a portable charger,” Fortenbery said. “School police don’t look at us like students. They look at us like criminals. Police officers have no place in schools.”

A PSU petition calling for replacing the security force with community members trained in trauma care and restorative justice had more than 12,000 signatures by Friday morning.

Related Content

Observing Juneteenth: A march to the Art Museum, a fashion show, ‘Jawnteenth’

Pa., N.J., Del. and 44 other states officially mark June 19, 1865, when enslaved people in Texas first got news of the Emancipation Proclamation.

2 weeks ago

Trauma-informed approach

Philadelphia’s school security is now under the direction of former Deputy Police Commissioner Kevin Bethel, who is nationally known for his efforts to change how police deal with young people – away from arrest and punishment and toward trauma-informed and nurturing interventions. Bethel has promised to retrain existing officers and hire new ones who believe in his approach.

The officers, who are no longer called school police but instead school security officers, do not carry guns. The cost of the security force is more than $31 million.

Bethel said he is eager to sit down with PSU to discuss their concerns. While he was still on the city police force, he started a diversion program that has reduced school-based arrests by 80%.

The fervor of the speakers at the hearing “reaffirms the importance of allowing individuals to have a voice in the process,” he said in a text message after the hearing. “You cannot deny the energy and passion they brought to the conversation this evening. I think it is great, and I am hopeful we can turn these conversations into a productive collaboration.”

He has already met with another organization, UrbEd Inc., co-founded by 2018 Science Leadership Academy graduate and student activist Tamir Harper.

“We have to start removing police officers from our schools,” Harper told the board. “We can’t chant ‘Black Lives Matter,’ we can’t chant ‘no justice, no peace’ and not ensure that Black schools matter and Black children matter when they enter the buildings they’re going to in their neighborhoods.”

Metal detector policy

Harper also called on the board to abandon Policy 805, which makes the use of metal detectors mandatory in all District high schools. The board is getting ready to revise the policy at its meeting next week, at Bethel’s urging, to make the experience less stressful for students. Bethel is retraining officers to be friendlier and more respectful and will be posting signs to let students know exactly what objects and substances they are not permitted to carry into schools.

But Harper told board members: “You have the power to really remove metal detectors and look at reallocating the funding.”

Both Bethel and Board President Joyce Wilkerson have pointed out that removing metal detectors is not a simple matter, because although PSU and other advocates say they create a prison-like atmosphere, many parents and students say they feel that the detectors keep schools safer.

At the hearing, several adults who work in schools also backed the students’ position. Eighth-grade teacher Chelsea Maher said that having police in school is “hypocritical.”

“Police presence in school does nothing more than feed the prison industrial complex through the school-to-prison pipeline,” she said. “You’d rather support a racist system than reimagine school safety.”

Related Content

Portraits of Black fathers to light up Barnes Foundation this weekend

Portraits by West Philly photographer Ken McFarlane show the undersung love and strength of Black fathers.

2 weeks ago Listen 1:48

More should be spent on “community-building and mental health services,” she said. “Police officers in schools only instill fear in a majority of our students, which limits their learning.”

Charlie McGeehan, a teacher at the U School, said, “It’s time to take up PSU’s calls to remove school police.”

Teacher Eric Moran took a position closer to what Bethel is doing with school security. “We need to reevaluate the structure and function of our school police officers,” he said. “While there are some great people doing this work who … mentor and work with our youth outside of the school day, they’re also bound by protocols and directives that inhibit their autonomy when a serious incident occurs. Instead, they need to be re-imagined as a de-escalation force to help our young people and nurture them rather than punish them.”

Annike Sprow, a social worker with Lakeside Institute, has worked in city schools to train teachers in trauma’s effects on the brain. She said, “The mere presence of police in schools has a negative impact on healthy brain function in students who are Black and brown and have to deal with the chronic stress of living in overpoliced neighborhoods. … It’s impossible to become a truly trauma-informed district without the removal of school police.”

Activists who have led successful de-policing efforts in Toronto and elsewhere also addressed the board.

Jessica Alacantara, an attorney with the Advancement Project, a civil rights organization based in Washington, D.C., said her organization works “all across the country and found the same thing to be true: There is no evidence that police in schools make children safe.”

Instead, she said, they need “the supports already proven to improve school climate, like counselors, social workers, conflict de-escalators, behavioral specialists, and restorative justice practitioners.”

Eyes on September

Beyond policing, students and other speakers told the board that the focus in September should be on equity and safety, steering funds towards student supports with an eye toward correcting long-standing inequities.

“As we plan for a scarier future, the board must look for investments that will build resilience” among students, said Alfredo Praticò, a recent District graduate, former student school board representative, and chair of the Philadelphia Youth Commission. He called for increased spending on counselors, tutors, and other support staff tasked with helping students stay on track.

“The pandemic has already claimed too many lives,” said Praticò. “We cannot allow the children of Philadelphia to be the next casualties.”

Stephanie King, a Northern Liberties parent who has battled segregation in her community’s schools, told the board that its pandemic plans should directly confront well-documented inequities among District schools. Everything from enrollment policies to library funding should be on the table for reform, said King.

“You cannot kick this can down the road forever,” said King, whose children are two of the very few white children at Kearny Elementary.

“You cannot pretend that we are giving all students an equal chance,” she said. While schools like Central have “a library that looks like something out of Harry Potter, my school’s library looks like boxes of books.”

District officials are considering several re-opening scenarios and recently set up an online survey for families and community members. At the board hearing, veteran parent advocate Cecelia Thompson told the board that the District’s survey “does not fully address the concerns of families.”

Thompson said the survey doesn’t give families enough room to weigh in on specific concerns, including questions about special education students and those with medical needs. Parents seeking answers about social distancing and other policies find little in the way of answers, Thompson said.

“They are afraid there will be 30-40 students in a classroom, and they don’t want that in the time of COVID,” she said.

Among the things that parents need to know is how school schedules will line up with work and transportation schedules, Thompson said. Social distancing won’t be easy if adults and students are all commuting at the same time.

Transit is “a big concern,” said Thompson. “Will the School District have different start times so that SEPTA is not jammed with students and adults going to work?”

Speakers repeatedly reminded the board to remember the needs of working parents as the District re-thinks school schedules.

Parent Naheerah Camps told the board that women, in particular, could be hit hard by changes. Many are the primary earners for their families, she said, and the demands of “hybrid” and online-only schedules could force them to choose between going out to earn a paycheck and staying home to provide child care.

“We are the household breadwinners,” said Camps. “Who’s going to pay the bills when the kids are home three days a week?”

Another theme among the speakers was trauma. They called on the board to be ready to help students handle what could be a difficult return to school.

Harper, of UrbEd, said that if students are only going to be in class part-time, that time should be spent on work that helps “restore the community” and work through issues of equity and justice.

“Students feel unheard, unsafe, and discouraged,” said Harper, and next year’s classroom agenda should aim to restore their trust.

More ideas for the fall

Among the speakers’ other suggestions for September:

- They called on the District to make sure its emerging plans for September are calibrated to support students forced to quarantine because of new infections in their school, home, or community. “We have to build in flexibility for kids who can’t come back to school” because of viral concerns, said Ben Perkins, a teacher at North Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion High. “No matter which plan we have, we’re going to have kids who are going to have to self-quarantine.”

- Speakers noted the importance in September of sustaining and expanding extracurricular programs. This will be particularly important if students are on their own during the week due to staggered schedules, they said. “A reason students seek out trouble is a lack of options,” said Alisia Flemings of the Philadelphia Youth Commission. “Research shows that music programs have improved development, increased IQ, and raised test scores.”

- Recent District graduate Jessica Bernal told the board that schools need plenty of staff next year to make sure that the resources made available get used. Filling the library or opening a computer lab isn’t much help if there’s no librarian or tech specialist to help students use what’s there, she said. At Philadelphia High School for Girls, Bernal said, “I was never able to use all the resources because there was no staff.”

- McGeehan of the U School called on the District to formally endorse the Caucus of Working Educators’ “Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action.” First launched four years ago, the Caucus’ effort has been “endorsed by Philadelphia City Council and many school districts across the country,” said McGeehan, a Caucus of WE member. “It is time for the Board of Education and the School District of Philadelphia to formally recognize and support this week of action.”

Board seeks community advisors

At the close of Thursday’s hearing, board officials noted that they are seeking three to four new members for the Parent & Community Advisory Council. Applications for the unpaid positions are available on the District website and due July 10. Board member Letitia Egea-Hinton said that applications from parents citywide are welcome, but that the board is in particular need of representatives from Northwest and South Philadelphia. The council has no formal powers, but members have a chance to shape District policies, Egea-Hinton said.

“The advisory council has been instrumental in helping the board as we think about our goals and guardrails,” she said.

About Letters for Black Lives

Letters for Black Lives is a set of crowdsourced, multilingual, and culturally-aware resources aimed at creating a space for open and honest conversations about racial justice, police violence, and anti-Blackness in our families and communities.

We began as a group of Asian Americans and Canadians writing an intergenerational letter to voice our concerns and support for the Black community. We have since grown to include other immigrant groups and communities of color. Our goal is to listen, support, and amplify the message of Black Lives Matter within our communities.

We encourage people from all communities to adapt and build off of these resources.

viewers will receive a reading of the Hmong version of the Letter for Black Lives project which was translated in 2016. #LettersofBlackLives For more information on the Letter for Black Lives project, go to: lettersforblacklives.com Daim nov yog daim ntawv lus Hmoob sau los ntawv Letters for Black Lives (Tsab Ntawv rau Neeg Dub Txojsia) thiab yog ib qhov dej num uas yuav muaj mus rau yav tom ntej uas muaj lub homphiaj los txhais ntaub ntawv qhia kom tsis txhob pub kev ntxub neeg Dub los rau hauv peb haiv neeg thiab zej zog. Nws sau los ntawv kev koomtes nrog lub koomhauv #BlackLivesMatter (#NeegDubTxojsiaMuajNqis). Thiab daim ntawv no yog kev koomtes los ntawv coob leej ntau tus ua xav pom kom peb muaj kev sib tham txog qhov teebmeem ceemtseeb no nrog tej niam tej txiv thiab cov laus ua los ntawv kev siv hwm thiab saib tau ib leeg ib tug. Original Letter (English) Dear Mom, Dad, Uncle, Auntie: Black Lives Matters to Us, Too: Mom, Dad, Uncle, Auntie, Grandfather, Grandmother: We need to talk. You may not have grown up around people who are Black, but I have. Black people are a fundamental part of my life: they are my friends, my classmates and teammates, my roommates, my family. Today, I’m scared for them. This year, the American police have already killed more than 500 people. Of those, 25% have been Black, even though Black people make up only 13% of the population. Earlier this week in Louisiana, two White police officers killed a Black man named Alton Sterling while he sold CDs on the street. The very next day in Minnesota, a police officer shot and killed a Black man named Philando Castile in his car during a traffic stop while his girlfriend and her four-year-old daughter looked on. Overwhelmingly, the police do not face any consequences for ending these lives. This is a terrifying reality that some of my closest friends live with every day. Even as we hear about the dangers Black Americans face, our instinct is sometimes to point at all the ways we are different from them. To shield ourselves from their reality instead of empathizing. When a policeman shoots a Black person, you might think it’s the victim’s fault because you see so many images of them in the media as thugs and criminals. After all, you might say, we managed to come to America with nothing and build good lives for ourselves despite discrimination, so why can’t they? I want to share with you how I see things. For the whole letter, go to: https://lettersforblacklives.com/dear…

George Floyd death: ‘The same happened to my son’

By Jessica LussenhopBBC News, Minneapolis

- 15 June 2020

Related Topics

Youa Vang Lee was at her home in Minneapolis when her son showed her the video of George Floyd dying under a police officer’s knee. Lee, a 59-year-old Laotian immigrant who assembles medical supplies at a factory, heard Floyd cry out for his mother. It triggered a deep and familiar pain.

“Fong was probably feeling the same way, too,” she said in Hmong, her eyes filling with tears. “He was probably asking for me, too.”

In 2006, Lee’s 19-year-old son Fong – who was born in a refugee camp in Thailand – was shot eight times by Minneapolis police officer Jason Andersen. The officer remains on the force to this day, a fact that the Lees were not aware of until told by the BBC. The officer was terminated twice, but has apparently since been rehired.

Although security footage showed Lee was running away at the time, Andersen claimed the teenager had a gun. A grand jury declined to indict him and the police department ruled the shooting justified. The family sued in civil court claiming excessive force and brought evidence the gun found beside Fong’s body was planted. An all-white jury found against them.

Youa hadn’t spoken publicly about her son in over a decade, not since the family came to the end of their legal road with nothing to show for it. But after Lee saw Floyd’s death, she began asking if anyone knew of marches she could attend.

“I have to be there,” she said.

- Inside the community at the heart of the protests

- ‘I’m Asian, so I can never be American’

- Timeline of US police killings

Although no one directly discouraged her, some members of her community questioned the decision. The Twin Cities, as Minneapolis and St Paul are known, are home to the largest urban population of Hmong in the US, many of whom came to the area as refugees in the 1980s and 90s.

The Hmong are an ethnic group from South-East Asia, with their own language, mainly drawn from southern China, Vietnam and Laos.

Within that community, there has been heated debate about how to respond to the Black Lives Matter and Justice for George Floyd movements, which are demanding systemic change to policing.

For Youa Lee, however, there was no debate. She wanted to get involved for one reason – when Fong died in 2006, the first people to show up in support of her family came from the black activist community.

“They were the loudest voices for us,” recalled Shoua Lee, Fong’s older sister. “Even before we asked for help from other communities, they had come to us and offered their help.”

Although four officers have been charged with the murder of George Floyd on 25 May, the viral video of the incident only captures two of them – former officer Derek Chauvin, who kneeled on Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes, and former officer Tou Thao, who kept the crowd back, rather than going to Floyd’s aid.

“Don’t do drugs, guys,” Thao said at one point to distressed onlookers.

Thao, an 11-year veteran of the department, has been charged with aiding and abetting second-degree murder. He is also Hmong.

As soon as Boonmee Yang, a fourth-grade public school teacher in St Paul, saw the video, he knew things were going to get complicated in the Hmong community.

“Oftentimes, it’s always been black victims at the hands of white officers. But now that someone else who looked like me was also involved in this, it made me really concerned,” he said.

As a Hmong activist, Yang said that it hasn’t always been easy to publicly express solidarity with the black community. He said some suffer what he calls “sheltered Asian syndrome”, meaning they rarely interact with others from outside the Hmong community, and that their knee jerk response was to defend Thao’s actions.

There is also a history of conflict between the two communities, particularly in the early days of resettlement, according to hip-hop artist and activist Tou SaiKo Lee. Refugee families often wound up in the Frogtown neighbourhood of St Paul and in East St Paul, areas that have historically had large African American populations.

“There was conflict between youth. Fights between new immigrants, new refugees and those that are currently living in the neighborhood – I was a part of that,” he recalled. “There’s some that still hold that tension.”

Unlike the more broadly defined “Asian American” demographic, the Hmong community has a much shorter history in the US. Almost half of the Laotian Hmong fled their country in 1975, after the fall of Saigon in the Vietnam War. For 15 years, the CIA recruited thousands of Hmong soldiers to fight a so-called “secret war” against the North Vietnamese, but after the US pulled out without providing an evacuation plan for their allies, those who cooperated with the Americans, or were perceived to have, fled. Some were killed by the communists, thousands wound up in Thai refugee camps.

- ‘Pandemic of racism’ led to George Floyd death

- Viewpoint: US must confront its Original Sin to move forward

- Police v Public – an awkward conversation

Tens of thousands were resettled in Minnesota, an overwhelmingly white state with few resources for the new immigrant population. Without the ability to speak the language, many could not find work. Today, the Hmong population in the US actually has much in common with the African-American population in terms of socioeconomic and other quality of life factors.

According to figures from the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center, one in four Hmong Americans lives below the poverty line. While 50% of the broader category “Asian Americans” have graduated university, only 17% of Hmong Americans have a college degree. And while 72% of white families own a home, less than half of Hmong Americans and African Americans do.

The Hmong community has also long struggled with interactions with police. Initially, there was no Hmong representation among its ranks. Officers struggled to understand and to serve the new population. In an infamous 1989 case, a police officer shot two sixth-grade Hmong boys in the back as they ran away from a stolen car. The officer was never charged.

Tou SaiKo said he was often racially profiled by Minneapolis police as a teenager, at one point spending two nights in jail after an officer found a fishing knife in his trunk. He said he was never charged, but he remembered getting pulled over many times and asked “What gang do you affiliate with?”

“I’d say, ‘I’m a college student,'” he recalled.

Still, those common struggles between the black and Hmong communities did not prevent old tensions from leaping to the fore in the aftermath of Floyd’s death, particularly as looting and property damage hit Asian-owned businesses in the Midway neighbourhood of St Paul.

“Tou Thao” is a very common Hmong name, and many who share it with the indicted officer faced online threats and harassment.

And as young Hmong activists – in particular women and members of the LGBTQ community – attempted to express support of Black Lives Matter, they faced condemnation and vitriol from within their own community, even threats.

Annie Moua, a recent high school graduate, saw plenty of comments online within her Asian American political groups that she calls “anti-black”, saying things like “all lives matter” and asking, “They never helped us during our protest – why do we need to help them?”

“During that week I lost a lot of friends,” she said.

It was during the worst of that online fighting that Yang got a Facebook invite from a friend to join a group called “Hmong 4 Black Lives.” There were only three members at the time. “I was on it,” he said.

He saw that a large Black Lives Matter demonstration was planned at the Minnesota State Capitol the next day, and created an event page for the nascent group. By morning, there were 300 members of Hmong 4 Black Lives (as of this writing there are now over 2,000).

By afternoon the next day, a group of about 100 Hmong activists had gathered at the capitol, carrying signs that read, “I’m a Thao and I stand with Black Lives Matter” and “I am Hmong and for BLM – period”.

For 18-year-old Moua, it was her very first protest, and after the amount of turmoil she’d witnessed online, she was scared. “I was very, very nervous,” she said. “I did not know what was going to go down.”

Among the marchers was a small, elegant woman in a face mask and a baseball cap – Fong Lee’s mother, Youa.

After fleeing their farm in Laos, and four years of waiting in a refugee camp in Thailand, Youa and her husband dreamed of giving their children a brighter future in the US.

America was supposed to be a refuge. She never dreamed her middle son would wind up dead at the hands of a police officer.

“I feel like it was a mistake to bring my children here,” she said in Hmong, translated by her daughter Shoua. “Now my son is gone.”

Fong Lee was 19 years old when he went for a bike ride on 22 July, 2006. He was with a group of his friends in the parking lot of Cityview Elementary, a school in North Minneapolis, when officer Jason Andersen and a state trooper pulled up in a squad car.

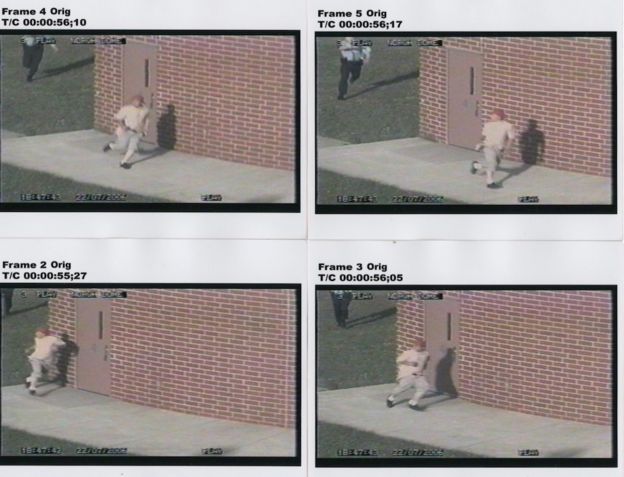

The boys took off running, with Andersen following Fong. A security camera from the school captured the final moments of the chase – Fong runs from the parking lot around the corner of the school, and Andersen is seen close behind with his gun pointed at Fong. Though blurry, the security footage does not clearly show a gun in Fong’s hands, a fact that Andersen acknowledged at trial.

In the final frame, Fong is seen lying on his back, bloodied and unmoving. He was hit four times in the back.

Almost as soon as the news broke, Al Flowers, a longtime Minneapolis activist who has sued the police department multiple times over charges of brutality, started showing up to protests – at the school, at the courthouse. The Lees always saw him and another activist, the late Darryl Robinson of Communities United Against Police Brutality. They didn’t ask to show up, Shoua Lee said, they just showed up.

For his part, Flowers said that after years of fighting for justice in the killings of black men and women, he believed that because Fong was Asian, there was a greater possibility that the officer would be convicted.

“We felt like he was treated like we was always treated,” Flowers recalled. “[We thought] he’s going to get justice. And then he didn’t. So we were shocked.”

Mike Padden, the Lee’s family attorney in the civil case, said losing the case even with surveillance camera footage and the strange history of the gun recovered at the scene has always troubled him.

“In 2009, the environment for suing cops was way different than it is now,” he said. “It bothers me. It was probably the most disappointing case in my career.”

An old, Russian-made Baikal .380-caliber semi-automatic handgun was found about three feet from Fong’s left hand, free of fingerprints or blood.

In 2004, a man reported his gun stolen in a burglary. He was later told by Minneapolis police that his gun had been recovered in a snowbank and it would be in police custody until an investigation had concluded. The gun matched the serial number on the Baikal .380 caliber found by Fong Lee’s body.

When that was pointed out at trial by Padden, the police provided an explanation — the gun found in the snowbank was not the Baikal .380. There had been a mix-up with the identification and the paperwork, and the Baikal had never been in their custody.

The Minneapolis Police Department did not respond to questions from the BBC about the case.

Andersen was back on the street two days after Fong’s death. The Minneapolis police chief later awarded him the department’s “medal of valour” for his actions that day.

The Minneapolis Police Department tried to fire Andersen twice after that – once after he was arrested for domestic violence, and once after he was indicted by federal investigators for kicking a teenager in the head during an arrest. The domestic violence case was dropped due to lack of evidence, and a jury acquitted Andersen in the assault on the teenager, despite the fact that other officers had reported his actions that day as excessive. Minneapolis’ powerful police union helped get Andersen rehired.

The union is often cited as the reason why it is so difficult to fire officers with problematic records. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing, the city of Minneapolis is trying to take on the union by withdrawing from negotiations.

Andersen is still an employee of the Minneapolis Police Department, and serves as the chaplain coordinator. Social media posts show him handing out donations, like car seats, bed sets and kitchen supplies to needy families in Minneapolis.

In a brief phone call with the BBC, Andersen confirmed that he is the same officer from the Lee shooting and referred all questions to the department’s media spokesperson.

“It’s something that’s been put in the past and I know that was very, very hard for them because they lost their son,” he said of the Lees. “I care for the family a lot and they went through something traumatic.

“Both of us had to live through this so when this gets dug back up, it’s probably – it’s something they never want to hear about again.”

It was Tou SaiKo Lee who asked Youa if she’d like to come to the state capitol, march with Hmong 4 Black Lives and speak about her son. It’d been almost 10 years, and Tou was also worried that bringing the case back up might be too traumatic.

But her answer was instantly, yes.

That day, as they walked towards the capitol steps to join the larger Black Lives Matter group, Youa was in front, walking silently as the younger Hmong participants chanted around her.

At some point, someone handed her the microphone. Even though she couldn’t do it in English, she spoke passionately about supporting George Floyd’s family and the movement that was born in his name. She promised to do anything she could for the Floyd family.

“We have to join hands with them,” she told the crowd. “We come here to beg for justice and righteousness.”

She wept openly, bringing many gathered around to tears as well, even those who could not understand her.

“Without Fong Lee’s family it would just be Hmong people bickering back and forth,” said Tou SaiKo. “Many people see their own mother in Fong Lee’s mother, many Hmong people, and so to see her in that emotional state, with those empowering words calling for solidarity, I thought that was a breath of fresh air.”

When told that Fong’s mother had joined the George Floyd protests, Flowers was pleased.

“I’m proud that she’s out there supporting,” he said. “My memory is watching her have to go through that and not understanding the law, not understanding what was really happening in the United States – that this could happen.

“We as African Americans, we knew what was the possibility and we knew that could happen. That was sad because we lost another case. That was another case we lost.”

And although not everyone in the crowd for the first ever Hmong 4 Black Lives march could understand her, according to Annie Moua, the person who took the microphone immediately after Youa summed it up perfectly.

“You don’t need to understand [Hmong] to know what this pain feels like.”

75 ways Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are speaking out for Black lives

“Many of us wouldn’t even be in this country, if not for Black struggles for justice,” one Asian American activist said.

A protester marches with a sign during the City Collective Prayer March on June 7, 2020, in Norfolk, Va.Annette Holloway / Icon SportswireJune 12, 2020, 2:19 PM EDTBy Natasha Roy and Agnes Constante

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing, teenager Mandy Zhang grew frustrated with the media. Its portrayal of the protests sweeping the country negatively shaped her friends’ and family’s perception of the Black Lives Matter movement, she said.

“Rather than focusing on the purpose of the Black Lives Matter movement and peaceful protests, the focus was on the violence and looting,” she told NBC News in an email.

So Zhang, a student at Walter Payton College Preparatory High School in Chicago, and some of her friends channeled their frustration into writing a letter to the Asian community in hopes of uniting Asian and Black communities, she said. They then decided to form the Dear Asians Initiative to continue these efforts and, with the help of volunteers from across the U.S. and Singapore, translated the letter into eight Asian languages.

“Without the leadership of Black Americans, we would not have been able to immigrate to the U.S. and start a new chapter in our lives,” it reads. “They helped us, and it is our time to help them.”

Like Zhang, many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders across the country have shown their support for the Black community and Black Lives Matter movement in the aftermath of the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and many other Black Americans.

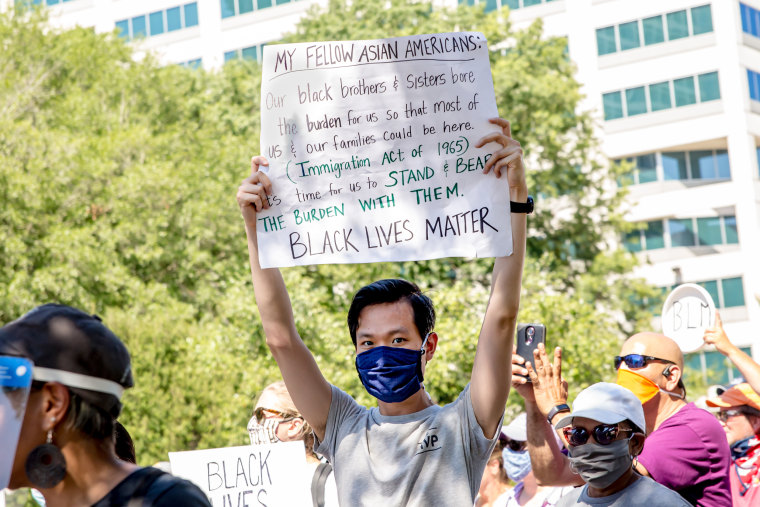

“So many of the social and political advances that Asian American communities have seen over the centuries have been the direct result of Black struggle and activism,” CJ Leung, a member of the San Francisco Bay Area group Asians4BlackLives, said in an email, citing the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, one of the gains of the Civil Rights Movement that enabled many Asian families to immigrate to the United States.

“Many of us wouldn’t even be in this country, if not for Black struggles for justice,” Leung added.

Here’s a look at some of the many ways the AAPI community has been showing solidarity with the Black community, from organizing and participating in protests to providing educational resources and fundraising.Events

The National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance hosted a phone bank on June 2, calling Minnesota lawmakers to demand for justice for George Floyd’s death. The group has also encouraged the community to share actionable resources with their networks, which includes agencies and individuals to call, what to say, and groups to support.